Liz Cain is one of many speakers we will have at SaaStock18 in Dublin, which takes place October 15th to the 17th. Read about the full agenda and then be sure to grab your ticket before prices increase on August 3rd.

There is a little secret Liz Cain has known for awhile about building outbound sales models: every company sucks at it, the first time around. It’s inherently difficult to make it work. It was as difficult when Liz built NetSuite’s BDR organisation from scratch. It is as difficult now. And one of her roles as a Partner at OpenView is to help the portfolio of companies succeed with it.

According to Liz, there are three major mistakes that every organisation makes as it builds out outbound sales models. One of them is how they run experiments.

When she mentioned that at a recent talk she gave, it was as if she had sucked the air right out of the room. The overwhelming sentiment was: We are not good at this. The questions that followed confirmed that even more.

The reasons are many, but Liz calls out ‘the squirrel problem’, or the nature of people to be easily distracted and drawn toward the next exciting idea, as a key contributor.

The squirrel problem

In its essence, the squirrel problem is not having the discipline to keep the experiment going long enough to see it produce any definitive outcome.

When Liz said it during her talk, everyone nervously laughed. “They were guilty as charged.”

“People are good at pivoting, often changing course faster than they should; but they are not good at the discipline of sticking with an experiment to see if it would work.”

Through the years, Liz has noticed that pattern. Companies would give an experiment a try but never really give it enough time to prove it right or wrong. Distracted by a shiny new idea or discouraged by not seeing results soon enough, they would abandon it. Efforts pivoted, rarely producing conclusive results and therefore rarely helping to find better ways to generate leads and sell.

The result was that not only did companies never really run experiments well but the people involved were convinced they were inherently bad at them.

Liz knows well just how important experiments are. Afterall, the success she achieved in her time at NetSuite started off as one big experiment. “If we hire graduates straight out of college as BDRs, give them inbound leads to work through, can we prepare them to take sales roles with million dollar quotas 9–12 months in the future?”

Put simply, she needed to figure out if NetSuite could successfully develop their next team of sales reps in-house to supplement external recruiting. When she first began to build that organisation, NetSuite’s revenue was ~$200 million. By the time that organisation grew to a well-functioning organisation of 170 BDRs, the company’s revenue had increased to almost a billion dollars and was about to get a record-breaking acquisition by Oracle.

What follows is Liz Cain’s framework for running lead gen experiments and sticking with them. According to her, using it as a roadmap will help with sustaining the discipline.

The Hypothesis

Every experiment needs to start with a hypothesis — a prediction or educated guess — which can be tested. Liz recommends a statement instead of a question, and this is where the source of discipline will originate as it helps bring focus to your work. For example, you might say “I will generate more opportunities by targeting the C-suite, than director-level contacts”.

You could have one hypothesis or ten. In fact, the more hypothesis you have, the better as long as you take the time to prioritise the tests you are going to run.

To generate them, Liz recommends approaching a few people such as the Head of Sales, the Head of Marketing, the Head of Product, a couple of sales representatives and ask them the key questions you are trying to answer — What do you think is going to be most effective way to get more qualified leads, what is our best performing customer segment, or what is the best level contact for an initial meeting? Don’t limit yourself to those roles, however; anybody else that directly touches the customer can bring valuable insights.

“As you talk to a number of people to generate your hypothesis, you will quickly realise that there are a few overarching themes. You start from there.”

Design the experiment

NOTE: Liz’s focus is on optimising outbound lead generation. In the following example, she assumes you have already defined your ideal customer profile, target segment and target contact. This framework can easily be extrapolated to cover other sales experiments.

The root of following through with an experiment is to set the parameters very clearly and the expectations very realistically so it makes sense to everyone involved and can be easily measured. Following are a few of the tenets to consider.

People involved

Most lead gen experiments need to start with minimum two people assigned to it. Anything less than that is inconclusive because you don’t know if it is the person or the experiment that is succeeding. This is particularly important when you are testing lead list creation.

Time

If the timeframe isn’t set realistically and followed through with discipline, the likelihood that the squirrel problem will manifest increases. You want to make sure that the timeline is adequate. With every company and every experiment how long that differs. There is no universal answer, but there are ways you can start figuring it out. The example Liz gives is with generating new lead lists:

- Ask yourself some important questions: How long would it take to generate a list, run through your standard lead touch plan and hear back from prospects?

- As you are trying to answer these, be aware of the bias most companies fall for: “No one sets the right expectation when it comes to results.” Liz recommends grounding your estimates in data — you can look at how long it currently takes you to do any of the above.

- Be realistic. If you are testing purely for the cost of lead acquisition, you can calculate those costs in real time. However, if you are tracking the performance of those lists, you need to allow time for outreach, response and the length of your sales cycle.

The levers

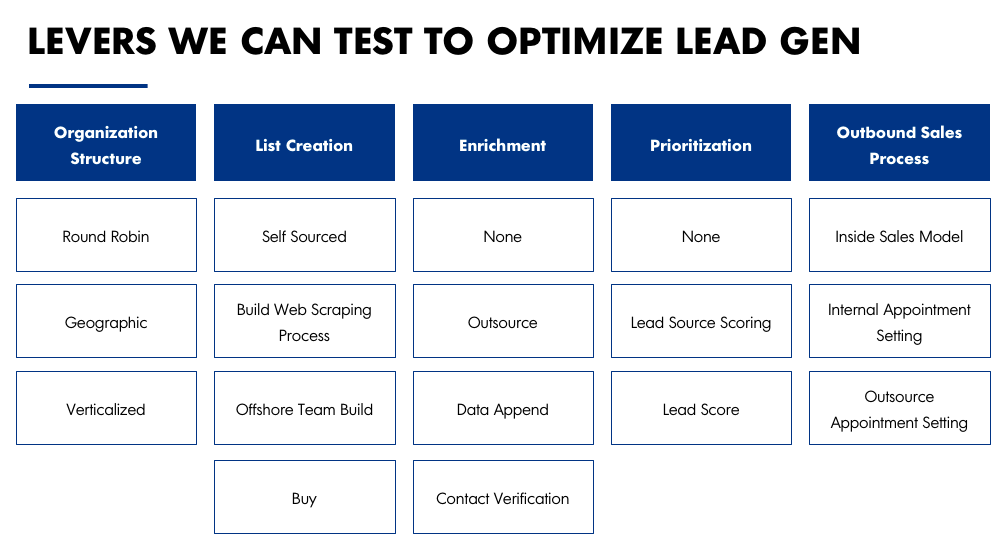

Once you have your hypothesis defined, it’s time to look at different levers to experiment with:

- Organisation structure. How do you organise your team around this? Is it round robin, geographic, vertical, company size or some other way that determines who gets to work on what.

- List creation. How are you getting the list — scraping it from somewhere, asking someone else to do it for you, is it built in-house or offshore,

- Enrichment. How are you populating the list with more information? Is it automatically or manually, is it outsourced, is it through LinkedIn, where would you buy it from?

- Prioritisation. Are you lead scoring, picking a certain geography/industry, do you assign who contacts who or do you let people select manually,

- The process. How are you contacting them — an inside sales model, Internal Appointment System, Outsource appointment setting, etc.

You start working through all these and begin to figure out what matrix model options makes the most sense and is the most efficient and cheapest.

You determine that by working with the data, you already have. What are you doing currently what is working, what isn’t? What are the current costs of acquiring the lead, what are the conversion rates through the funnel, what is the value of the customer long term?

Metrics

You have to have a clear way to define how you evaluate an experiment, and you have to agree to this measurement before you begin. Most people rely on subjective measurement which leads to over-estimating and over-reporting effectiveness.

“I often see people get one deal, get super excited about it, and start applying more resources.”

One proof point, however, is not indicative that an experiment was truly successful.

Again, it’s important to ask yourself some important questions:

- How much did it cost to acquire that lead? Alternatively, that customer?

- How did it compare to other ways of acquiring customers?

- What was the conversion through the funnel?

- What is the churn on these customers?

If you were evaluating the effectiveness of events instead of outbound lead tactics, the questions would naturally change. Be thoughtful in defining metrics and success for any experiment.

In a lead gen experiment, the metrics you choose will centre around the fully-loaded cost of acquiring a customer — the price of buying the list, enriching it with data, getting the BDRs to call to secure a meeting and then converting to a closed-won customer.

Revenue targets are the most common measurement and are ultimately what matters most to a growing business. However, it’s not always realistic to use the revenue to gauge the success of an experiment. If you have a transactional sale with an average sales cycle <1 month, this is your top metric. As sales cycle elongates, you need to look for leading indicators to determine if you are on the right track. You can attach another milestone to it, like getting a meeting for example. The metrics for an experiment should really stem from the parameters of your business.

After you have determined all of these, have someone objective in the mix to help you make sure that the metrics parameters make sense. “Salespeople and BDRs are a bit too deep in the day to day to be the only ones setting the parameters of the experiments.” That could be a sales operations or business analyst or even someone cross-functionally, looking in and giving the differing perspective. Liz also notes the recent proliferation of growth roles in software companies — someone responsible for driving experiments and aligning resources around these initiatives.

Evaluating costs

You will want to get as specific as possible here. What effort are you going to put in nurturing a lead to see if they convert? You need to outline it and make sure every contact follows it. “For example, you can call four times, email seven times, and contact once through Linkedin. If they do not convert at this point, you give up.”

The reason you are doing this is to have a clear action but also to evaluate the costs you will incur, both financial and in terms of time. How much does the person get paid, how much does maintaining their desk cost, how much does acquiring the list cost as well as enriching it, how much time will it take them to go through each touchpoint.

Once you have all that in place, you can start evaluating the opportunities. This is where you figure out whether the experiment makes sense. Once you cross-reference that with the actual result you will be able to decide with confidence. Even if the cost per lead is low from the onset, if very few opportunities arise from it, it doesn’t make sense to continue with it.

A caveat

Be aware of experimenting with something that seems cheap on the outside. Buying a very broad list and not taking the time even to enrich it properly is one example. You won’t have any insight into whether they are in an active buying cycle or if they’ve done any recent research about you or any of your competitors. When you email these leads, you will end up having to message them with something quite broad because all you know is each person’s job title, company and which product of your kind their organisation uses. The success rate will be very low.

Run the experiment the right way

With all this in place, you still have to prepare yourself that it will be tough to keep the discipline to keep going with it. No matter how determined you start off with, distractions will come so be hyper-aware of them, expect them and still push through the temptation.

“Commit resources for the length of this.”

It will look like it’s going sideways. Don’t divert, hold the steering wheel.

That starts from following the all-important timeline. Liz knows well how tempting it is to cut things short rather than have the allocated resources for the designated days. She has been working with one of the portfolio companies where two weeks into a designed experiment, they said; “We need to reallocate resources” This obviously compromised the experiment.

Another reason to keep the discipline is because things do take time. To see conversion, you may have to touch 20 times. Wait and don’t jump to conclusions.

If you are changing throughout the experiment, change only one lever. During a recent experiment that one of the portfolio companies did, they were testing the impact on qualifying leads based on where they acquired the list and how they enriched it. To come up with a conclusive result, they had a good sample from each list and went through the entire cycle of touchpoints. They worked simultaneously on a few lists with the same people, applying the same scripts and techniques.

After they had found the winning combination of acquiring a list and enriching it, it was time to make the final decision whether they should double down on it or not.

Review

It’s where the all-important part of the review comes in. It aims to answer one important question — if a particular experiment worked, how far can it scale. You have to be painfully honest whether it worked or not. It should not be ad-hoc but instead planned with the right set of people evaluating.

Once you have found your list source then you start putting all efforts into it: more money into getting the list, more time into enriching it, more BDRs in contacting the people, etc. If you have run your experiment well, it will be the gift that keeps on giving. “In NetSuite, I found a lead source that served fantastically for over three years. It scaled forever.”

A culture of experimentation

To keep this going, you have to foster a culture of experimentation. How do you foster it?

- Encourage creativity and trying new things

- Assign a person to lead the experiment whose enthusiasm and relentless efforts are setting an example for everyone else.

- Clearly denounce retaliations if there is a failure.

- Compensate the people involved regardless of the results of the experiment

- Be clear that experiments are a way to be better collectively. Experiments in the first place come from a belief that things are not optimal and there is a search for becoming more so.

Moreover, remember that outbound sales experiments are not only for the sales organisation. Try to include as many customer-facing roles as possible such as marketing, lead gen, customer success, customer support and others.

How many experiments should you run at the same time? As anything else in this piece, there is no one correct answer. However, here is a rule of thumb example straight from NetSuite’s experience.

Remember, Liz was in charge of 170 BDRs. The maximum amount of experiments spread between different pockets that she did was 4. These people have other things to do, and one person should be involved in only one experiment. A team of ten can be involved in only one experiment.

Liz accidentally fell into sales. After listening to some advice, she knew if she wanted to move into a leadership role she had to figure out where the revenue comes from. So when given the opportunity to lead a team of salespeople, Liz took it. Everything she has learned is through doing experiments and being disciplined about them.

Liz is one of many speakers we will have at SaaStock18 in Dublin from October 15th to the 17th. Read about the full agenda.